The excentrics

Pages

Welcome

Live steam models on 7¼" gauge of the Württembergische T3 and on 5"gauge Great Eastern Railway Y14 class

Welcome to this blog. It will inform you about the progress of designing and building live steam model locomotives. The blog contains the description of a model Würrtembergische T3 on 7¼" gauge (constructed between 2006 and 2017), the wagons for this loco (built between 2018 and 2022), and the current project a 5" gauge model of a Great Eastern Railway Y14 class loco (started in 2020)

On the left you'll find the index where you can browse the different articles and on the right you'll find all the extras. You'll find a brief description of my other locos on the top tabs.

T3 7¼" steam locomotive

Wednesday, 26 June 2024

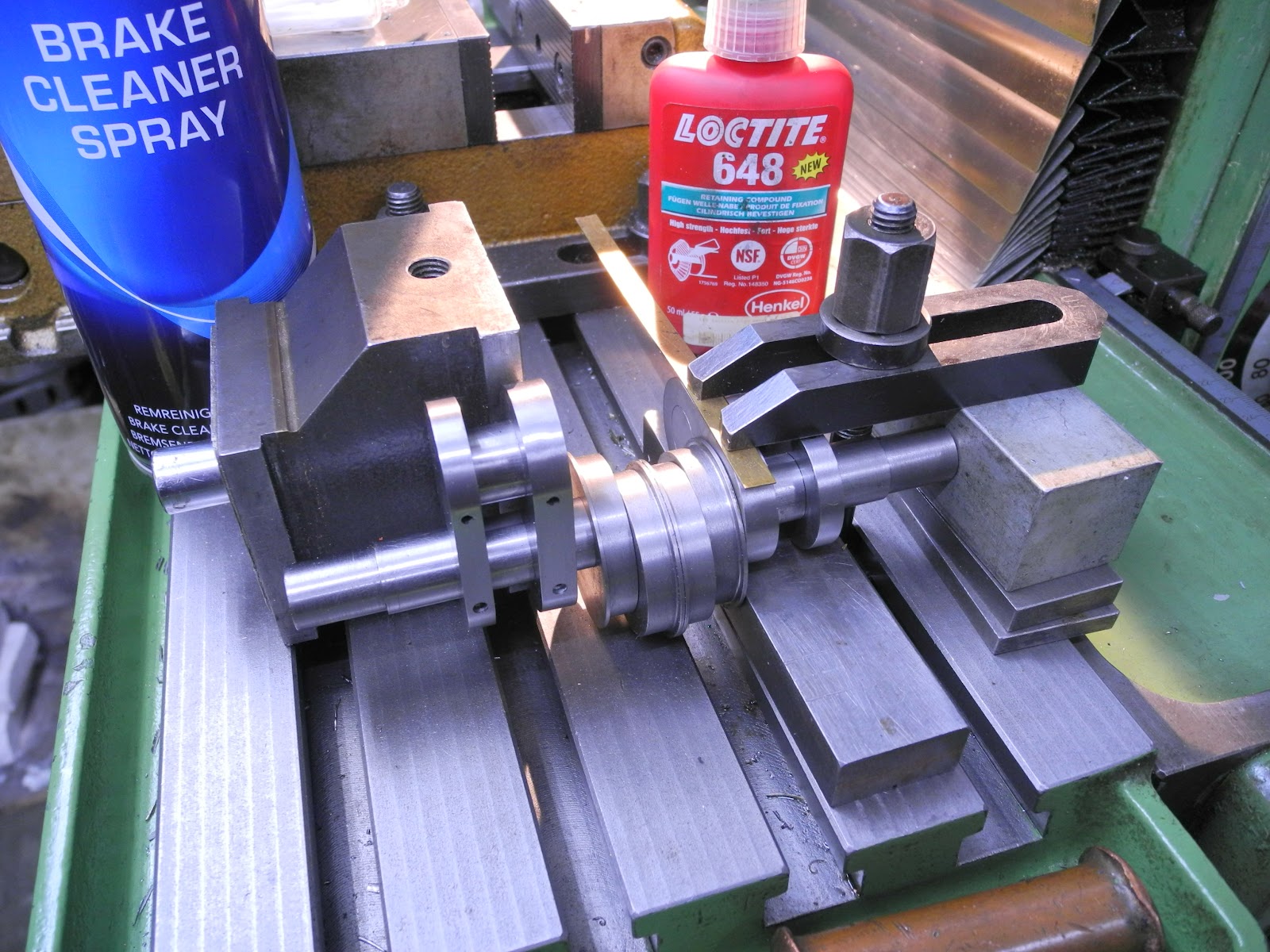

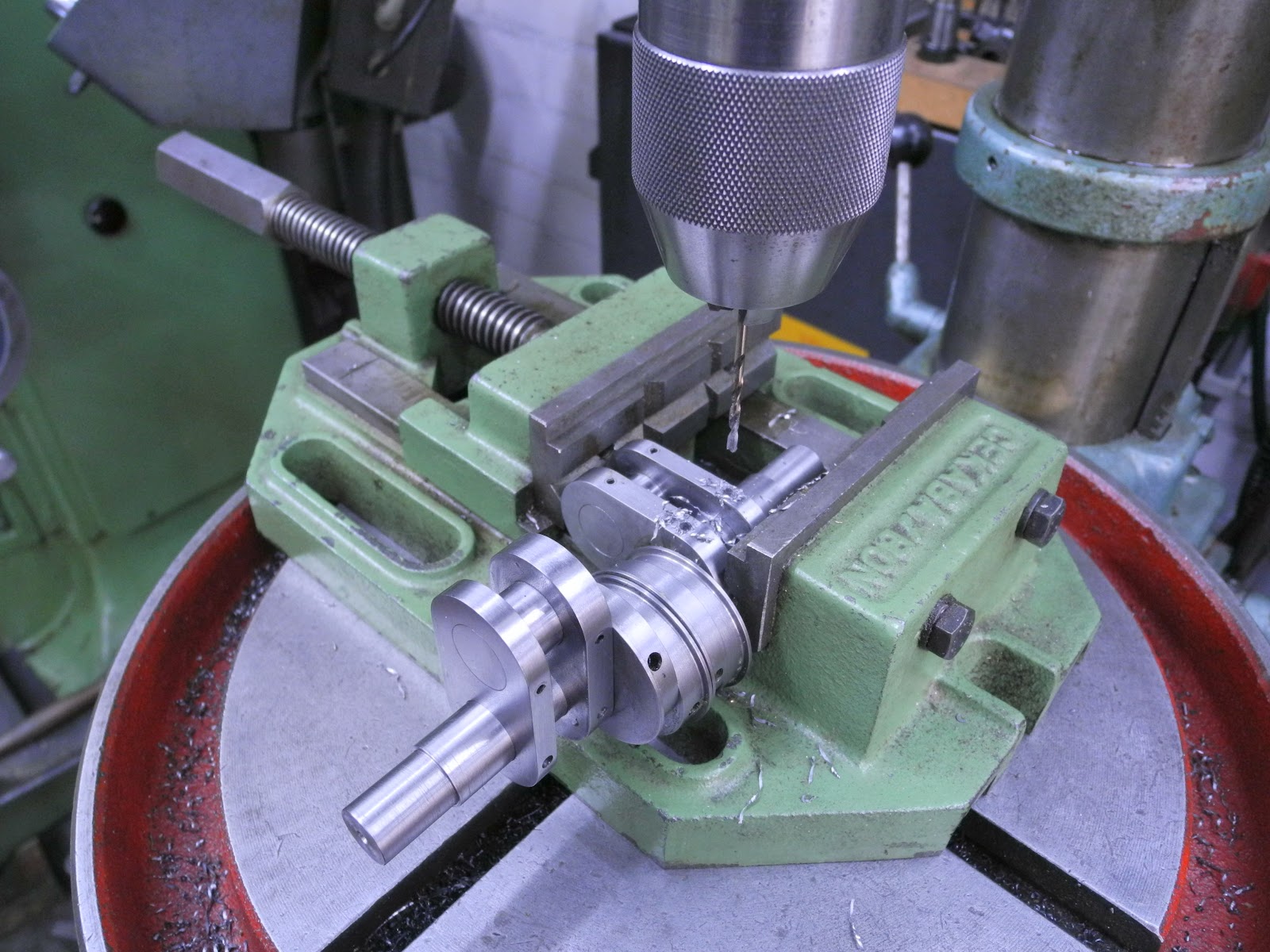

Crank axle

Tuesday, 18 June 2024

Driving and coupled wheels for the Y14

As an intermezzo in building the boiler, some machine work was nice to do. Turning the driving and coupled wheels is a straightforward turning job, but requires some planning in set-up and sequence to machine the several faces.

The wheels were bought in England from Mark Wood, in the days before the Brexit customs rules made this very difficult.

The wheel castings are of excellent quality and are fine cast. Mark did some special research on the prototype Y14 locomotive so that they are very close to scale.

Update: Mark told me today that:

Just after Brexit I had problems with long customs delays and even parcels being returned to me - that was with DPD. Now I use UPS and pay the local duties in advance and parcels have been delivered to Europe in about 3 days from posting.

So this gives a good prospect for future model locomotives. 😀 Take a look at his website, because he offers many wheel castings.

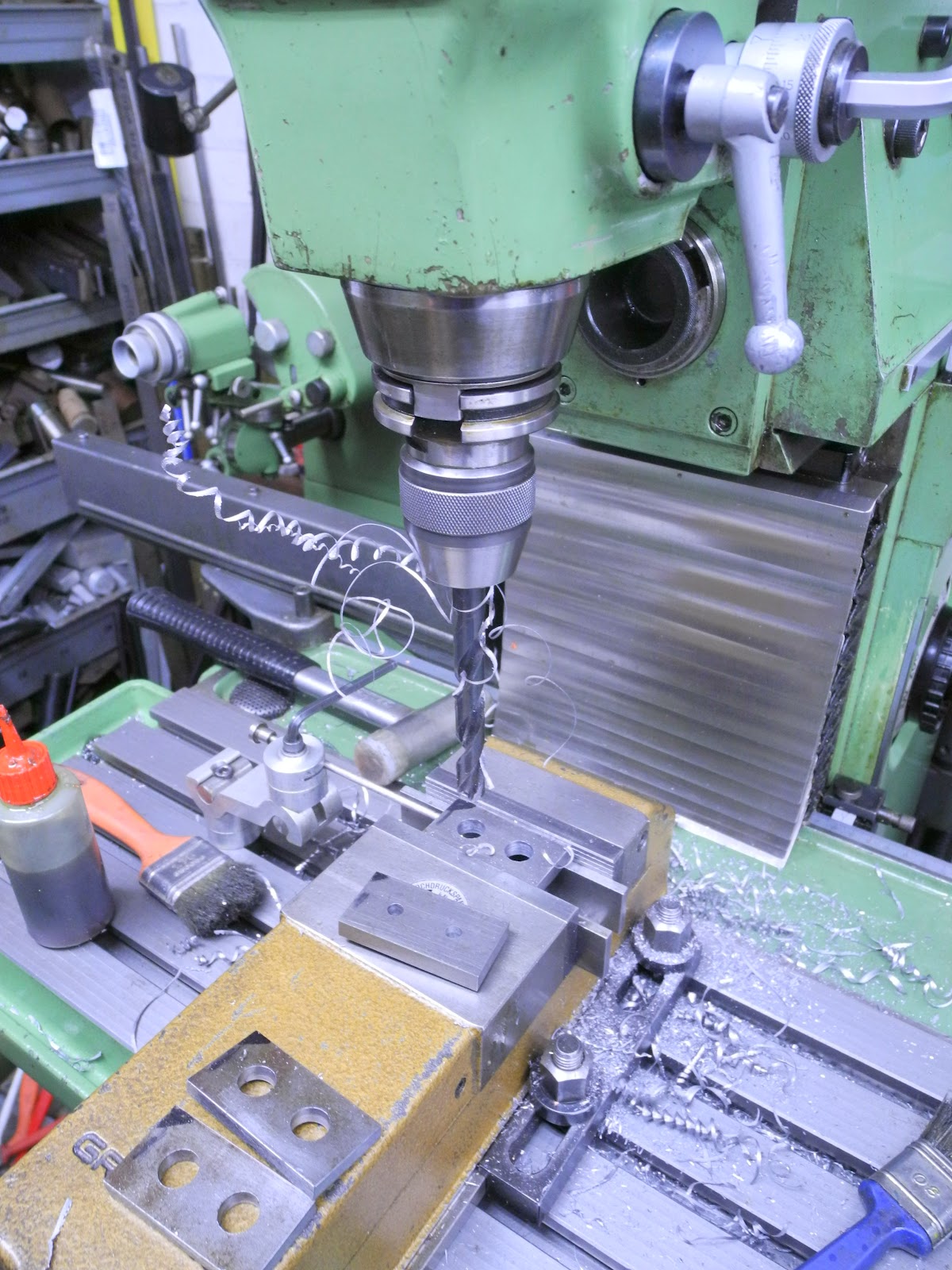

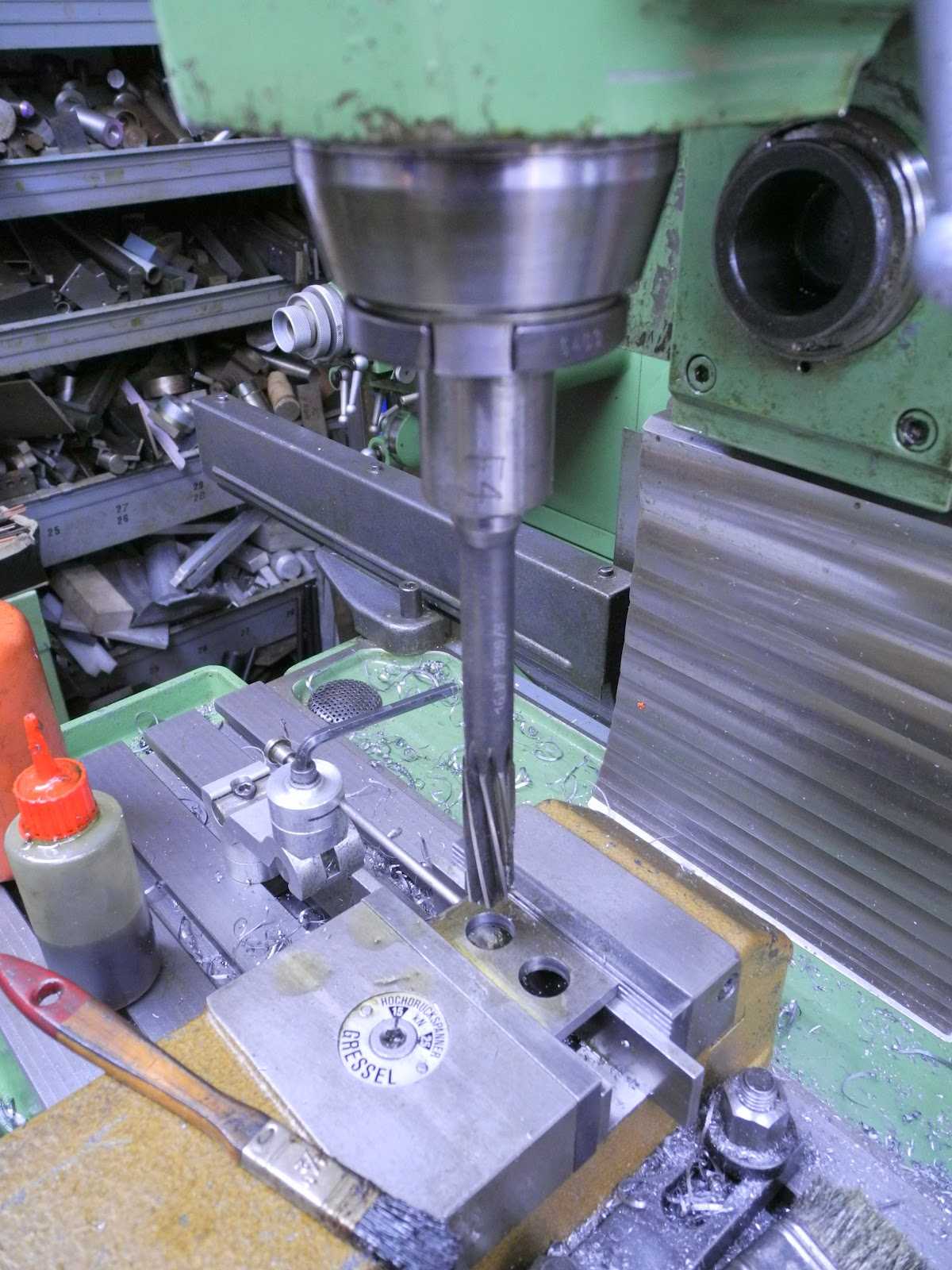

The stroke of the crankpin was done first with a center finder used on the stub, setting this to zero and then moving the Y-axis to 26,5 mm.